Executive Summary

ISS World is a trade fair and training series on lawful interception, signals intelligence and electronic surveillance, held five times per year by the Virginia-based company TeleStrategies Inc. While Dr. Jerry Lucas, President of TeleStrategies, has stated that ISS World does not permit ‘attendees from Iran, North Korea or Syria,’ the organization appears to have allowed the attendance of Sudanese, Iranian and Syrian entities, including a Sudanese company designated by the United States government for links to human rights violations.

TeleStrategies’ activities are opaque, registration is invitation-only and restricted to telecommunications companies, equipment vendors and government officials. Much of what is known is the result of documents obtained by international privacy organizations through conference attendees. The high cost of entry brings two substantial benefits to participants: 1.) connecting with surveillance technology vendors on the state of the art; and 2.) training on industry practices and equipment, including providing a “Certificate of LEA/Intel Communication Monitoring and Surveillance Training Completion.” Documents released last September disclose attendees for ISS World’s global 2012 events. Within this document, as well as documentation from previous years, several governmental and corporate entities from Iran and Sudan are attributed as having attended.

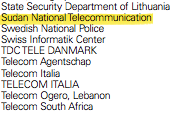

The United States has maintained a comprehensive sanctions regime against Sudan since 1997, administered through the Department of the Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC), in response to alleged connections to terrorist organizations and human rights abuses committed by the government of President Omar al-Bashir (31 CFR § 538.205). The American embargo disallows the provision of services to Sudan, which ISS World would fall under as a private training and trade series. Under the descriptions of telecommunications and governments in attendance that are provided within these TeleStrategies documents, eleven Sudan entities are described:

- Government Sudan (2012)

- Governmental LEA (2012)

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2012)

- Sudanese Embassy in Malaysia (2012)

- Sudan National Telecommunication Authority (2008)

- Sudan Ministry of Interior (2007)

- Sudan Telecom (2012)

- Sudan Zain Telecom (2012)

- Sudatel (2012)

- dolpy (2012)

- Sudan Canar Telecommunications (2012)

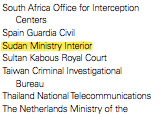

Registrants must participate in support of larger, pre-screened organizations, and cannot be present within a private, personal capacity. In the case of Sudan, TeleStrategies has indicated knowledge of the participant’s nationality through its disclosed attendance records. Six of the listings are entities of the Government of Sudan, and three of which, recorded as ‘Governmental LEA,’ ‘Sudan Ministry of Interior,’ and ‘Sudan National Telecommunication Authority’, are directly cited within the State Department’s Human Rights Reports as parties in the country’s online and offline human rights abuses. Additionally, Sudatel, a telecommunications company primarily owned by the government, was designated by OFAC as a Specially Designated National under its [SUDAN] program well before attendance.

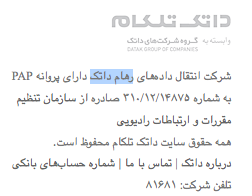

Similar to Sudan, the United States maintains a comprehensive trade embargo against Iran due to regional destabilization, nuclear enrichment activities and human rights abuses, amongst other issues (31 CFR §560.204). Additionally, the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions and Divestment Act of 2010 (CISADA), debars entities found to be facilitating Iran’s censorship apparatus from receiving federal contracts. This was expanded under President Obama’s April 2012 Executive Order on “Grave Human Rights Abuses by the Governments of Iran and Syria Via Information Technology” (the GHRAVITY E.O.), which imposes sanctions on any entity found to be providing either country with interception technologies. Based on available documentation, we identify two Iran entities in attendance, the country’s largest Internet service providers:

- Shatel (2012)

- Roham Datak (2008)

Datak was amongst the first entities designated under GHRAVITY, for having “collaborated with the Government of Iran to provide information on individuals trying to circumvent the government’s blocks on Internet content, allowing for their monitoring, tracking, and targeting by the Government of Iran.” In its designation, OFAC further noted that “Datak has demonstrated the intent and specific planning to purchase intercept equipment for Internet and voice communications.”

Additionally, the technologies on display and trained on at ISS World are increasingly controlled by the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security for National Security, Surreptitious Listening and Crime Control reasons. Vendors frequently offer samples of intrusion software or technical data, which may be controlled. The implementation of 2013’s Wassenaar Arrangement proposals on network surveillance and intrusion software augurs further potential difficulties for conference attendees and vendors.

Our sample of lists produced by TeleStragies itself only covers a minority of ISS World programs. However, we describe the reported attendance of public security entities from countries under targeted OFAC programs, within Crime Control restrictions and on lists maintained by the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. These documents begin to describe an organization and industry whose activities increasingly run contrary to the human rights and security policies of the United States government and multinational agreements.

Introduction

TeleStrategies Inc.’s ISS World, an abbreviation of Intelligence Support System, purports to be “the leading Lawful Interception, HiTech Criminal Investigations and Intelligence Gathering” in the world, with 4,635 attendees from 110 countries in 2012 alone. The main seminar and trade fair series, held five times per year across different continents, has been a frequent target of criticism by civil society organizations over the organizer’s lack of transparency or accountability on the inclusion of human rights abusing entities, as well as its promotion of highly-aggressive law enforcement practices whose place within even countries that adhere to democratic practices and rule of law remains debated.1

ISS World has from an early age asserted itself as a focal point for the marketing and sales of surveillance technology internationally. In a July 2003 editorial in an telecommunications industry publication, entitled “Making Money with ISS,” TeleStrategies cites growing markets abroad as one of three opportunities for return on investment ahead investment for equipment manufacturers,

Some governments in the Asia-Pacific region don’t even know how to spell privacy. Why will this drive ISS? The largest new markets for telecommunications equipment are in Asia-Pacific. You won’t be able to sell into these markets shortly without ISSs to support lawful and/or other kinds of interception. Asia-Pacific will create an ISS market on its own.”

These practices and allegations have earned the event the dubious nickname of the “Wiretapper’s Ball.” While civil libertarians have criticised the conference for its opacity in controlling for human rights, little attention has been paid to the relationship between TeleStrategies and the evolving foreign policy and regulatory regimes of the United States. Taking into account both long-standing prohibitions on trade with specially-designated countries and entities, as well as recent controls on technologies particular of concern, questions arise about the exposure of TeleStrategies and vendors under the ISS World series, given the exchange of technical data and facilitation of technology transfers.

What little is known about the content and participants of ISS World is the result of leaks of conference material through public transparency groups, such as Privacy International and Wikileaks. A survey of agenda tracks, such as “Mobile Location, Surveillance and Signal Intercept Product Training,” listed for the March 2014 Dubai conference2 elucidates ISS World’s role in the provision of sophisticated telecommunications surveillance and censorship as a turnkey commercial service, enabling more governments to run their own NSA-style intelligence programs. Moreover, sessions purporting to offer live demonstrations of “unrivaled attack capabilities and total resistance to detection, quarantine and removal by any endpoint security technology” begin to align with Congress’s mandate in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2014 to curtail the proliferation of cyber weapons through unilateral and cooperative export controls.3

These conferences and sessions, which include participants from American economic and political rivals, come at a time when James Clapper, then Director of National Intelligence, has written to the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence that,4

In addition, a handful of commercial companies sell computer intrusion kits on the open market. These hardware and software packages can give governments and cybercriminals the capability to steal, manipulate, or delete information on targeted systems. Even more companies develop and sell professional-quality technologies to support cyber operations—often branding these tools as lawful-intercept or defensive security research products. Foreign governments already use some of these tools to target US systems.

Therefore, as concerns over the threat posed to national security by the sale of surveillance technologies comes to the forefront of news and government reports, the central role of ISS World in facilitating their unrestricted, global proliferation requires deep examination by civil society and export control organizations alike.

Dr. Lucas, President of TeleStrategies, has previously claimed that the conference has ‘barred Syrian or Iranian government representatives’ and later that it does not allow ‘attendees from Iran, North Korea or Syria.’ Outside of these three countries, he has admonished journalists that ethical concerns are “not our responsibility.” However, the actual legal obligations of companies such as TeleStrategies engaging in international trade exceeds such voluntary measures, with respect to both the countries and the types of entities barred from participation. Moreover, beyond statutory prohibitions, the United States maintains country-specific reporting requirements pertaining to the transfer of technology or training on censorship or monitoring of the Internet. Finally, export control organizations and other governmental agencies have begun to implement new rules on the transfer of surveillance technologies, such as those proposed in both the December 2012 and 2013 Wassenaar Arrangement Plenary sessions. The participation of countries with notorious track records of human rights abuses, as documented by reports from the United States’ Department of State and Commission on International Religious Freedom, highlights critical policy considerations posed by TeleStrategies and equipment vendors’ activities at ISS World.

Given the recurrent administrative and legal expressions of concern over the international flow of surveillance technologies, we review potential areas of regulatory concern on the operations of ISS World. To do so, we attempt to address specific facts on conference attendance sourced from publicly-available documentation to call attention their implications within longstanding federal policies. However, we caution that a full assessment of TeleStrategies would require a great deal more information than is currently available, due to their lack of transparency. Therefore, we conclude with outstanding questions and concerns that must be addressed by the company and American government agencies.

Countries Under Comprehensive Sanctions Regimes

Over the past two years, releases of sale brochures under the ‘Spy Files’ moniker have shed light on previously difficult to obtain information regarding the capabilities of commercial surveillance and censorship products that are often sold in the shadows. Less noticed in coverage of these releases was the disclosure by TeleStrategies of governments and companies that have participated in the seminars.5 These documents, although only covering a small subset of all ISS World events, reveal important trends and associations, including pairing companies whose technology was found to be used against human rights activists, such as Hacking Team and FinFisher, with the same governments targeting those individuals domestically and abroad. However, beyond these specific instances of harm, this documentation offers records of attendance by governments and companies whose participation would run contrary to American embargoes or fall under reporting requirements of federal regulations. The lists available paint a vivid picture. While State and Congress attempt to create high walls around the export of “sensitive technologies” and OFAC issues General Licenses to ensure that the United States sanctions does not create an unintended chilling effect on access to online communications, TeleStrategies’ conferences has facilitated technology transfers that are incompatible and antagonistic toward efforts to secure the free flow of information.

Whether or not ISS World is held in the United States, TeleStrategies would be subject to the Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctions regulations for activities conducted abroad. To this point, TeleStrategies Inc. and ISS World, across all event pages and within public business records, appears to retain solely the American contact addresses of,

6845 Elm Street

Suite 310

McLean, VA 22101

Additionally, registration for all locations occurs under the domain and branding of the issworldtraining.com (attributed to Drums, Pennsylvannia), and the administration of the event is linked to Tatiana Lucas, Director ISS World Programs. Interviews with TeleStrategies staff similarly reinforce the direct relationship between the company and all ISS World branded events. There is no evidence that ISS World maintains subsidiaries or partnerships that would distance TeleStrategies, Inc. from compliance with United States export regulations. TeleStrategies, as well as Dr. Lucas, Ms. Lucas and Matt Lucas, appear to be United States persons. They would therefore maintain liabilities if found to be conducting business with sanctioned countries and entities without an exemption or license. However, a database of OFAC license applications, current to February 2013 and only claiming withholding exemptions on 3.3% of entries, returns no results for queries on TeleStrategies, Dr. or Ms. Lucas, or ISS World.

ISS World’s closed registration and provision of technical services increases TeleStrategies’ exposure to obligation for proper due diligence. The seminars offered are not public conferences, attendance is invitation-only, and limited to individuals associated with a “Telecommunications Service Provider, government employee, LEA or vendor with LI, surveillance or network products or services.”6 Registrants must participate in support of larger organizations, and cannot be present within a private, personal capacity. TeleStrategies advertises ISS World as training seminars, including offering a “Certificate of LEA/Intell (sic) Communication Monitoring and Surveillance Training Completion.” Therefore, ISS World constitutes not simply an open forum, but the provision of a service that may include the release of technology and technical assistance, through the facilitation of instruction, skills training, working knowledge, or consulting services. Sessions held in Kuala Lumpur and Dubai appear to be an easy means for resident Embassies or subsidiary entities, such as those of Sudan and Myanmar, to attend local sessions. ISS World’s consistent misattribution of potentially violative attendees calls into question whether the company maintains compliance processes to guard against questionable transactions or whether they engage in meaningful due diligence processes on registration claims.

Reported Attendees from OFAC Sanctioned Countries

| Entity | Session |

|---|---|

| Sudan | |

| Government Sudan | 2012 (2013 Brochure) |

| Governmental LEA | 2012 (2013 Brochure) |

| Ministry of Foreign Affairs | 2012 (2013 Brochure) |

| Sudanese Embassy in Malaysia | 2012 (2013 Brochure) |

| Sudan National Telecommunication Authority | Prague 2008 |

| Sudan Ministry of Interior | Dubai 2007 |

| Sudan Telecom | 2012 (2013 Brochure) |

| Sudan Zain Telecom | 2012 (2013 Brochure) |

| Sudatel* | 2012 (2013 Brochure) |

| dolpy | 2012 (2013 Brochure) |

| Sudan Canar Telecommunications | Dubai 2008 |

| Iran | |

| Roham Datak ** | Dubai 2008 |

| Shatel | 2012 (2013 Brochure) |

| * Designated under OFAC Sanctions At Time of Attendance | |

| ** Later Designated under OFAC Human Rights Sanctions |

See the Documents:

- ISS World 2006

- ISS World 2006 Fall

- ISS World Dubai 2007

- ISS World Washington 2007

- ISS World Dubai 2008

- ISS World Europe 2008

- ISS World Americas 2009

- ISS World 2013

Sudan

The United States has maintained a comprehensive sanctions regime against Sudan since 1997, in response to alleged connections to terrorist organizations and human rights abuses committed by entities associated with the government of President Omar al-Bashir. Under Executive Order 13067 issued by President Clinton, the United States imposed a trade embargo against the entire territory of Sudan and a comprehensive blocking of the assets of the Government of Sudan. As with the other four comprehensively sanctioned countries, Cuba, Iran, North Korea and Syria, these regulations included a prohibition on exportation of goods, technology, or services by U.S. persons to Sudan, as well as restrictions on performing services for Sudanese entities. Additionally, OFAC maintains a program of targeted sanctions against individuals and entities found contributing to the conflict in the Darfur region, under a Specially Designated Nationals (SDN) List.

The Sudanese government has struggled to reconcile control over the Internet, against an increasingly technologically-sophisticated public. While Sudan does not impose the same form of overt controls as China or Iran, in its 2013 Human Rights Report on the country, the Department of State notes that:

The government regulated licensing of internet and telecommunications companies through the National Telecommunications Corporation (NTC). The NTC blocked some websites and most proxy servers judged offensive to public morality. Generally there were no restrictions on access to news and information websites, but authorities sporadically blocked access to YouTube. During the late September protests, the government blocked most internet service for 24 hours.

However, beginning in March 2014, statements from the National Telecommunications Corporation appear to suggest that Sudan will increase its control of the Internet to block “negative websites.” Currently, it appears that the Sudanese government leverages network interception technology for surveillance purposes rather than for filtering. Previous research has documented the deployment of censorship-capable network technologies manufactured by North American companies on Sudanese networks. However, it is believed that more sophisticated surveillance infrastructure has been provided through the expansion of involvements by the Chinese telecommunications vendors Huawei and ZTE. All surveillance vendors believed to be active in Sudan have participated in ISS World.

Despite American sanctions regulations, as well as Sudan’s track record on regional destabilization and human rights violations, TeleStrategies lists 11 Sudanese entities as having attended ISS World, 6 of which are governmental agencies, in addition to all major telecommunications companies. One of these companies, Sudatel, was designated under the SDN program on May 29, 2007 as having contributed to the government’s campaign of violence in Darfur. Additionally, two, the National Telecommunication Authority and Ministry of Interior, have a direct and documented roles in the violation of the fundamental rights of privacy and expression online and offline. State’s Human Rights Reports further notes the role of the Ministry of Interior in internal security and threats against media. Finally, these participants are confirmed by a 2008 program schedule that highlights Canartel’s participation on a panel on Regional Developments on Lawful Interception.

The implications of Sudan’s potential attendance at ISS World, and the reality of the event as an interception training program, becomes clear when taken against conference tracks within seminars that Sudanese government representatives were known to have attended. For example, the Dubai 2007 ISS World, attended by the Sudanese Ministry of Interior, featured a session on “Practical examples of Lawful Intercept” conducted by Blue Coat Systems Vice President Craig Hicks-Frazer, promising that:

This speech will discuss the options available to authorities to intercept web traffic (both HTTP and encrypted traffic), the technology required and placement options. Examples will be used that include blocking pornographic content across the Middle East, Internet Watch Foundation blocking of child pornography in Europe and sites that promote terrorism. The depth of functionality will be discussed for individual URL blocking, reverse lookups, HTTPS blocking and updates. Options for logging, blocking Skype and peer-to-peer traffic and collating traffic logs will be discussed.

Similarly, the Prague 2008 ISS World attended by the National Telecommunication Authority offered sessions on “Interceptions And Retained Data: How To Manage Huge Amount Of Data With An Analysis Tool,” “Mobile Forensic Analysis For Smartphones” and “Remote Forensic Software.”

Iran

Similar to Sudan, the United States maintains a comprehensive trade embargo against Iran due to regional destabilization, nuclear enrichment activities and human rights abuses, amongst other issues. As struggles for democratization played out online in Iran, and then Syria, the role of censorship and surveillance in violations of human rights led to the adoption on additional sanctions and reporting requirements related to the transfer of such technologies to both countries. The first example of this was the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions and Divestment Act of 2010 (CISADA), which required the Government Accountability Office to report entities facilitating Iran’s censorship apparatus in order to debar them from receiving federal contracts. This was expanded under President Obama’s April 2012 Executive Order on “Grave Human Rights Abuses by the Governments of Iran and Syria Via Information Technology” (GHRAVITY), which was then codified by Congress under the Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act of 2012.7 GHRAVITY imposes sanctions on any entity, including extraterritorially third-party nationals, found to be providing Iran and Syria with interception technologies. BIS has also used civil penalties and the denial export privileges against parties implicated in the transshipment of Blue Coat devices found to be at the core of Syria’s censorship regime.

Despite assurances regarding the nonparticipation of the Iranian government, we believe that TeleStrategies has allowed at least two Iranian Internet Service Providers to attend, based on telecommunications companies listed under the names Roham Datak and Shatel on TeleStrategies’s “ISS World EMEA” program for 2008 and its Global “Program Schedule for Year 2013” brochure, respectively. While Shatel is attributed to the United Arab Emirates, this listing would correspond to one of the largest Internet providers in Iran, also named Shatel. There is no indication of a non-Iranian entity within the UAE operating under name Shatel, and the company’s involvements in Dubai trade conferences is amply noted elsewhere.

Despite assurances regarding the nonparticipation of the Iranian government, we believe that TeleStrategies has allowed at least two Iranian Internet Service Providers to attend, based on telecommunications companies listed under the names Roham Datak and Shatel on TeleStrategies’s “ISS World EMEA” program for 2008 and its Global “Program Schedule for Year 2013” brochure, respectively. While Shatel is attributed to the United Arab Emirates, this listing would correspond to one of the largest Internet providers in Iran, also named Shatel. There is no indication of a non-Iranian entity within the UAE operating under name Shatel, and the company’s involvements in Dubai trade conferences is amply noted elsewhere.

Roham Datak is particularly illustrative of the foreign policy issues presented by ISS World. Dr. Lucas’s differentiation of governmental and commercial entities does not make sense legally or operationally, given that rendering a service to an entity within an embargoed country would run afoul of OFAC sanctions, if not the mandates of CISADA and GHRAVITY. This lack of distinction between governmental and commercial in Iran is reinforced by the signaling of Treasury from the outset of GHRAVITY. Upon the Executive Order’s release, OFAC designated DATAK Telecom under human rights sanctions (SDN list) for conducting surveillance activities on behalf of the Iranian government and participating in the August 2011 DigiNotar attack against Iranian Gmail users:

The Iranian Internet service provider Datak Telecom (“Datak”) has collaborated with the Government of Iran to provide information on individuals trying to circumvent the government’s blocks on Internet content, allowing for their monitoring, tracking, and targeting by the Government of Iran. Datak regularly collaborated with the Government of Iran on testing surveillance techniques.

Over the last two years, Datak facilitated ongoing technical surveillance on Iran-based users of a popular commercial email service, designed to monitor and track the activities of its users. Datak undertook plans to carry out this type of attack on a larger scale, to potentially include surveillance of millions of Iranian users.

Moreover, Datak has demonstrated the intent and specific planning to purchase intercept equipment for Internet and voice communications.

DATAK Telecom is the same entity that participated in ISS World Dubai 2008 under the name Roham Datak, one year before the brutal crackdown on reformist and pro-democracy activists that brought the Iranian government’s repression of the Internet onto global stage.

Outside of this direct relationship to ISS World, public reporting and federal investigations on the export of surveillance technologies to Iran routinely focus on the role of Iranian telecommunications companies as the means for security agencies to acquire such equipment. Whether or not affiliations with sanctioned countries or entities were known to company, TeleStrategies would maintain legal and moral liabilities in performing proper due diligence. Based on available documentation, despite supposedly tightly-controlled registrations, TeleStrategies’s allowance of Sudanese and Iranian entities to participate in ISS World would have led training of these governments and companies on sensitive technologies. This would facilitate human rights abusing governments, and companies instrument to the government, to institute advanced applications of existing interception efforts. In light of the human rights components core to all current sanctions regimes, for policymakers and federal agencies, the activities of TeleStrategies appear to continually runs contrary to United States foreign policy interests.

An Increasingly Regulated Market

On June 20, 2013, the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) issued Export Control Classification Number (ECCN) 5A001.f.2, based on export regime changes agreed upon within the Wassenaar Arrangement’s December 2012 Plenary Meeting. This rule for the first time regulated the exportation of equipment “designed for the extraction of client device or subscriber identifiers (e.g., IMSI, TIMSI or IMEI), signaling, or other metadata transmitted over the air interface,” commonly known as IMSI Catchers. The IMSI Catcher rule fell within a broader class of technologies specially-designed as mobile telecommunications interception or jamming equipment, which are controlled by BIS for National Security and Anti-terrorism purposes.

Three months later, at ISS World Americas, NeoSoft AG presented a session entitled “IMSI/IMEI Catcher with Public Number Detection. CDMA Catcher,” within a track on mobile location, surveillance interception and analysis of mass geo-location data. ISS World facilitates the transfer and training of technologies that fall under the jurisdiction of the Export Administration Regulations administered by BIS as “Communications Intercepting Devices,” in addition to national security controls, and within the Wassenaar Arrangement’s recently proposed controls on “IP network surveillance systems” and “Intrusion Software.” The services and venue provided by ISS World and vendors increasingly run into ‘deemed export’ question, given release of data and technology that is more and more considered by U.S. export control laws as controlled. Involvement by American corporations and persons in ISS World presents questions on the management and release of controlled information to foreign nationals within the territorial United States and abroad. The argument follows that, despite not involving the direct export of physical equipment, current and forthcoming BIS controls on the surveillance technologies discussed at ISS World present exports considerations based on their application to ‘virtually any means of communication to the foreign national, including telephone conversations, email and fax communications, sharing of computer data, briefings, training sessions, and visual inspection of equipment,’ including through ‘merely hosting foreign nationals on a company visit or training.’8

The Tip of the Iceberg

In its explanation on Datak, Treasury notes a critical point undermining the validity of TeleStrategies’ government agency prohibitions. ISPs are subject to coercion from governments through licensing requirements and force of law. Datak’s role in facilitating technology transfers would not appear to be an unusual situation. Telecommunications companies across the world are forced to maintain their own surveillance infrastructure under the mandate of ‘lawful interception,’ which is then made available by request or directly operated by national security services. This is the Asia-Pacific market trend referenced in Dr. Lucas’s editorial piece. The lack of an independent judiciary or questionable national security authorities in such countries thereby renders the distinction between governmental and private moot. If a government engages in offensive security and human rights practices that warrants barring from ISS World, then all companies and persons subject to their legal compulsion and compliance apparatus must be prohibited as well.

OFAC maintains additional sanctions programs involving the Balkans, Belarus, Myanmar, Cote d’Ivoire, Cuba, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq, Lebanon, Liberia, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Syria, Yemen and Zimbabwe, and thematic programs on Rough Diamond Trading, nuclear enrichment, international narcotics traffickers, Foreign Terrorist Organizations, Terrorism List Governments, transnational criminal organizations, and weapons of mass destruction. These programs and their compliance requirements are ever evolving and often ambiguous. OFAC maintains restrictions against support of the security forces and regime entities for several countries that participate in ISS World, including Zimbabwe (Government Telecommunications Agency, Postal and Telecommunication Regulatory, POTRAZ Agency Telecom, South Africa Broadband, Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission, and the Zimbabwean Embassy in Malaysia) and Myanmar (Myanmar Police and Embassy Myanmar in Malaysia). Given recent changes in these companies programs, the lack of specificity in TeleStrategies’ documentation of attendees and dates of participation, it is unclear whether violations have occurred, but their participation is worth note and further investigation.

As described by OFAC, the Burma sanctions program began in May 1997, based on a determination by the Clinton Administration that the Government of Burma had committed large-scale repression of the country’s democratic opposition. However, the Burmese program, unlike comprehensively sanctions regimes, has been limited to specific economic transactions and military junta entities, and underwent easing starting in May 2012 after signs of political reform. Although the Burmese military remains sanctioned for human rights violations, the SDN list that the instructs much of its actual implementation is sparse on details and names for exact organizations and individuals of concerns. Despite limited programs and détente policies, concerns about continued human rights abuses and the availability of such technologies became more tangible when Blue Coat devices were found on the network of Burmese ISP Yatanarpon Teleport, providing authorities both censorship and surveillance capabilities. Zimbabwe is subject to similar restrictions on members of the country’s government, and other persons undermining democratic institutions and processes in the country, but not subject to blanket prohibitions on transactions with the government as a whole.

The legal considerations surrounding events like ISS World exceed both OFAC sanctions and BIS export controls, and extends further into Congresssional legislation. Similar to GHRAVITY’s provisions on surveillance and censorship technologies to Iran and Syria, Congress maintains reporting requirements for those found to facilitate human right abuses by some foreign governments. In January 2012, President Obama signed the Belarus Democracy and Human Rights Act. The legislation reauthorized the Belarus Democracy Act of 2004 in light of December 2010’s election, widely considered fraudulent, and the government’s ensuing crackdown. The renewal updated previous reporting requirements on weapons technology and training assistance provided by other governments or organizations, including assistance provided for the Belarusian government’s efforts to control the Internet. However, despite these regulations, the Belarusian State Security and Belarussian Embassy representatives are documented as having attended ISS World on multiple occasions, beginning in 2008 and as recently as 2012.

These findings call into question whether the current body of regulations controling the provision of crime control equipment and communications intercepting devices to human rights infringing states remain effective and current. While the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) of 1998 imposes a variety of restrictions on countries found to have committed systematic, ongoing and egregious violations of religious freedom, ISS World permitted attendance by the near entirety of the currently designated ‘countries of particular concern’ (Burma, China, Eritrea, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Uzbekistan) and all of recommended new additions (Egypt, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Vietnam).9 Federal agencies and lawmakers maintain a responsibility to ensure that standing precedents on human rights, such as the Leahy Law on security assistance and the International Religious Freedom Act, are still able to address the modern instruments that governments use to violently repress religious and political dissent, as those conventions have sought to do for their direct, non-digital equivalents. Western governments must assert greater involvement in the due diligence on the surveillance and censorship industry within existing regulatory and accountability bodies

Understandably, the case of Shatel highlights the transshipment and attribution problems that have plagued broader enforcement of sanctions, as Iranian and Syrian companies have established extensive fronts for skirting embargoes. Moreover, ISS World’s circuit of locations appears conducive to attendance by foreign embassies and corporations that would otherwise attract attention by journalists, civil society or authorities if held in the United States or Europe. These opaque practices regarding attendance and due diligence are inimical to public accountability and legal compliance.

TeleStrategies and American federal agencies maintain a responsibility to ensure that ISS World has not engaged in actions that violate extensive regulations on sanctions, export controls, and human rights. As we note in our introduction, a thorough understanding of the transactions and transfers facilitated through ISS World requires more information than is available due to TeleStrategies’ intentional opacity. However, this structural resistance to transparency and cavalier public attitude may present questions about the engagements of both TeleStrategies and participants as the public record stands.

Given the material implications of these initial findings, it is incumbent on TeleStrategies to shed light on its practices and history, beginning with:

- Disclosing its full list of participants, including registration documentation, in light of potential misattributions by attendees;

- Clarifying which sessions and seminars representatives from sanctioned countries were allowed to attend, and whether the company sought or secured legal permissible for attendance by such parties;

- Detailing its participant vetting process that ensures beneficiaries are who they claim to be at the time of registration and at the time of the conference;

- Describing the mechanisms in place to ensure that it neither violates applicable laws nor provides material support for human rights violators and sponsors of terrorism.

Additionally, as export control organizations begin to recognize the implication of mass surveillance technologies, and regulate the products trained and promoted at ISS World, TeleStrategies and participants bear increasing obligations to control distribution of information and equipment for surveillance and content monitoring. TeleStrategies must address how current and future ISS World seminars will ensure compliance with such controls

Without such measures, TeleStrategies will remain perceived as an unregulated means for the transfer of technologies that challenges basic human rights commitments and operate outside of foreign policy interests.

Acknowledgements

This project would not have been possible without the consultation and support of a number of individuals, including but not limited to Sarah McKune and Privacy International.

Citations

-

http://www.yalelawjournal.org/forum/tiny-constables-and-the-cost-of-surveillance-making-cents-out-of-united-states-v-jones↩

-

http://www.issworldtraining.com/ISS_MEA/index.htm↩

-

http://beta.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/senate-bill/1197↩

-

http://www.intelligence.senate.gov/130312/clapper.pdf↩

-

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/ccc?key=0AonYZs4MzlZbdHhnSkJwelV1dHYxQnNPb2pUNk9zckE#gid=2↩

-

http://www.issworldtraining.com/iss_mea/Brochure01.pdf↩

-

https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/112/hr1905/text↩

-

http://www.hoganlovells.com/files/Publication/959a46aa-cde2-4afa-bbd1-e23b2b8a3c7b/Presentation/PublicationAttachment/ac1154b9-799f-4137-99df-e24b2ba967c8/Peters%20article.pdf↩

-

http://www.uscirf.gov/sites/default/files/resources/USCIRF%20AR%202013%20Transmission%20Letters.pdf↩